Managing Our Microbes

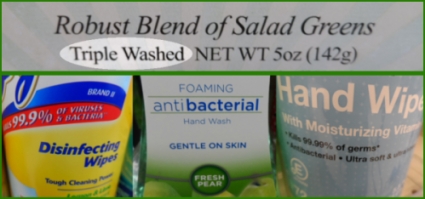

Walk into a grocery store and you'll see spinach that has been triple washed and foods wrapped tightly in plastic, as well as cleaning products that "kill 99.9% of bacteria."

Walk into a grocery store and you'll see spinach that has been triple washed and foods wrapped tightly in plastic, as well as cleaning products that "kill 99.9% of bacteria."

Before you step into the store you'll wipe your hands with an antibacterial wipe. In all likelihood this wipe will contain a strong antimicrobial agent such as triclosan, first introduced to America as a pesticide in 1969.

We are indeed the Super-Sanitized Generation.

Our obsession with hygiene is understandable. Bad things happen when people don't wash their hands or dispose of fecal waste in a responsible manner.

But has the pendulum swung too far? Are all microbes bad? Are we missing some key information that might help us turn the tide on increasing instances of allergies, chronic disease, and autoimmune conditions?

The truth is, our bodies are mostly microbial. Ninety percent, in fact. Microbial cells outnumber human cells by 10 to 1. Our bodies are a combination of fungi, bacteria, viruses, single-celled organisms called archaea, and probably other categories of microbes that will one day be named. Certainly not all of our inhabitants are "good," but is it possible that even the "bad" microbes help us in ways we don't yet understand?

Consider a healthy appendix. Once thought to be a meaningless organ, research suggests that it is a storehouse of beneficial bacteria, ready to share its microbial abundance when the body is in need.

Studies now show that babies get the majority of beneficial microbes in the birth canal—a finding with significant implications for children born by Caesarean section.

We now understand that antibiotics kill not only the bad microbes, but many of the beneficial ones as well.

The National Institutes of Health wants to find out more about the role of microbes in human health. In June 2012 it launched the Human Microbiome Project, which will study various microbial communities such as those found in nasal passages, oral cavities, and the gastrointestinal tract.

The Human Food Project, a crowd-funded initiative, is on a similar path, hoping to learn more about the connection between health and microbes.

What can we do in the meantime to arm ourselves microbially? Here are five suggestions for boosting your immune system by bolstering what some scientists call our "forgotten organ."

- Spend more time outdoors. Even our less-than-perfect outdoor air may offer some relief from microbes unique to indoor environments and expose us to healthier, naturally occurring microbes. A recent study conducted by the University of Oregon shows a microbial diversity in the air sampled on the roof of a local hospital, as opposed to a lack of diversity in the air sampled from mechanically ventilated rooms. Rooms with a window came out somewhere in between. The mechanically ventilated rooms had the greatest relative abundance of potential pathogenic bacteria. The outdoor samples were dominated by naturally occurring water and soil bacteria. On average, Americans spend 22 hours each day indoors. Why not make it 21?

- Use fewer chemicals on your skin and hair. Research suggests that any chemical applied to our skin will reach every organ in our body within 26 seconds. We are now realizing the potential for internal harm, but what about the vital communities of microbes present on the surface of our skin and scalp? If antibiotics kill the good as well as the bad microbes in the gut, can we assume harsh chemicals do the same to our skin flora? Even the Food and Drug Administration states that antimicrobials like triclosan are no more effective than soap and water. Why not try one of momsAWARE's all-natural, chemical-free soaps instead?

- Consume less meat from animals treated with antibiotics. According to the FDA, 80 percent of all antibiotics in the United States are fed to farm animals. What is this doing to the microbial communities in our digestive tracts? Antibiotic resistance may be one result. Researchers recently found 42 antibiotic-resistant genes in the human digestive tract that had transferred from antibiotic-treated livestock (see this article from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology). Eating meat from animals raised without the use of antibiotics may be one of the wisest things we can do to protect our delicate gut lining.

- Grow more of your own food. The mental health benefits of gardening are well known. Who can't benefit from time spent outdoors and the artistic satisfaction that gardening brings? But what about the microbial benefits? Researchers in the United Kingdom have found that the soil-based bacteria mycobacterium vaccae triggers the production of our "good mood" neurotransmitter, serotonin. A recent study published in the journal Nature shows that children in rural areas exhibit greater microbial diversity than those raised in urban areas, implying that gardening as well as playing in the dirt may have far-reaching health implications.

- Ferment more of your food. This is probably one of the easiest ways to boost your population of beneficial microbes. Food fermentation, while daunting for those new to the process (see A Fear of Fermentation), is making a comeback as many are realizing what humans have intuitively known for centuries. Lactic acid bacteria and many other strains derived from properly prepared sour milk products, sauerkraut, pickles, and other foods contribute to the trillions of microbes teeming with life in the intestinal lining. Kombucha, water kefir, and fermented lemonade make wonderful alternatives to sugar-laden soda drinks.

Want to learn more about the human microbiome? Check out the Human Food Project or pick up any of these resources:

- Good Germs, Bad Germs: Health and Survival in a Bacterial World

- Gut and Psychology Syndrome

- Honor Thy Symbionts

Managing our microbes may be one of the biggest keys to Living Healthy in a Toxic World.